A LAD INSANE: THE BOWIE PROJECT

“So, you go into some self-imposed 'Bowie bubble' for three weeks? That's what you do for fun nowadays?” asked my friend recently.

“Aw, don't lean on me, man, 'cause you can't afford the ticket,” came my delightedly snarky reply.

A LAD INSANE

That's right, I'm back from Suffragette City, having experienced the entirety of David Bowie's music catalog, all twenty-seven studio albums, chronologically. Oh, and a few live shows and documentaries to boot. Moreover, aside from listening to the music, I was also studying along with Nicholas Pegg's astounding 800-page “The Complete David Bowie” book that provides exhaustive, exceedingly well researched history, critical analysis, and anecdotes for each album and song (and every other artistic endeavor).

And nineteen days later, I emerged from my “Bowie bubble” and formally concluded my big “Bowie Project.”

The initial impetus for this idea came on the heels of my recent adventure to my beginnings in California's Central Coast, where me and my longtime friend fell into our favorite argument of whether “Hunky Dory or Ziggy Stardust” is the finest Bowie album.

It made me realize that I'd not actually actively listened to Bowie for a long while, despite the rather massive influence he and his music have had on my life. And I had intentionally avoided listening to his final masterpiece, Blackstar, as I just hadn't been ready to accept his passing back in 2016.

In addition, when “Let's Dance” dropped in 1983 and Bowie transmogrified from a unique sonic visionary to a world-wide pop star riding on a wave of banal, atrocious music he had no hand in writing, I completely tuned out. As such, there were plenty of albums in these dark years that I knew existed, but never got near enough to even know their names. So, with that, I cued-up 1967's self-titled album and thus began my freak-out in a, near 3-week, moonage daydream.

SOUND & VISION

I can't recall precisely how old I was when I first heard Bowie, but I do know it was “Aladdin Sane,” as my friend's brother played it incessantly and it was the 70s. Like many others, I was immediately sucked in and so began my strange fascination with David Bowie.

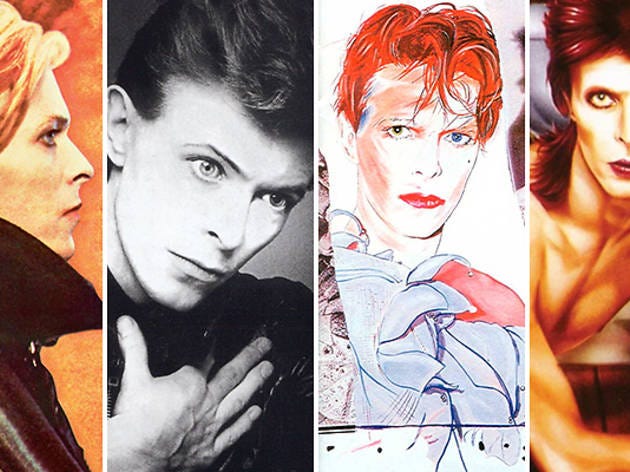

Bowie had an astonishing ten years of artistic brilliance and prodigious output during the 70s. Fueled by an intensive, near manic work ethic (and an equally prodigious amount of cocaine), the period beginning with 1971's “Hunky Dory” to 1980's “Scary Monsters...and Super Creeps” were, undisputedly, his best and most creative. From the Ziggified glam-rock bombast lasting through Aladdin Sane & Diamond Dogs to the glory of the experimental Berlin triptych consisting of “Low, Heroes, & Lodger,” it was such an amazing experience to listen through this section of the catalog. An absolutely unimpeachable series of documents of an artist so far ahead of the curve that it would take more than a decade for the rest of the world to catch up.

In listening to this period, as well as studying along with Pegg's book, two things became increasingly evident. The first of which is that Bowie's creative genius, inventive musicianship and song-craft is oftentimes overshadowed by his theatricality and the visual distractions of his characters like Ziggy or The Slim White Duke. Upon close examination, Bowie uses a very atypical, singular approach to chord structure and progression. So much so, that it is very distinct and it's usually present in most anything he writes by himself. It is a hallmark feature that really goes under-appreciated.

In addition, Bowie's unconventional use of instruments themselves is central to his unique sound and vision. While this can be detected within both his guitar and piano style, nowhere is it more evident than with his saxophone playing. It feels ephemeral, more like a brush of paint on canvas than its traditional place in a jazz or even rock band.

Throughout his career, Bowie was adamant and consistent in stating he was an artist who just happened to use rock music as a vehicle for expression. And that is shockingly clear when listening to the music and scrutinizing the lyrical content. An accomplished fine artist, Bowie has a keen, albeit understated ability, to take high-art or lofty, complex artistic ideas and “demean them down to a street-level,” as he once stated. This, as opposed to attempting to elevate low-art, which is the general approach in rock, is Bowie's secret weapon that comprises much of the magic he conjures when writing his music independently.

The combined effect of these two interrelated aspects help create an otherworldliness and near palpable sense of artful unwholesomeness that make Bowie's music exceedingly intoxicating and fundamentally unique.

ROCK 'N' ROLL SUICIDE

Sadly, 1980's stunning “Scary Monsters” marked the end of Bowie's visionary, progressive artistic assault. Having recently extricated himself from an appallingly onerous management contract where he'd been effectively robbed blind for the past decade, he was now finally in control of his royalties and had negotiated a multi-million dollar deal with a new record company. As a businessperson, I cannot fault him for intentionally desiring to craft an explicitly commercial record, which is precisely what occurred with “Let's Dance.”

Hiring “hit maker” Nile Rodgers, Bowie, for the first time in his career, wrote none of the music on an album. And it shows. It sounds exactly like every other one of the massive-selling, gold-plated turds that Rodger's has consistently shat out over the course of his production career. Which is why it was the biggest selling Bowie album to date and catapulted him to global superstardom. To quote Bowie at the time, “And off I go into the future with my career in my hands.”

How prophetic that statement came to be. For the next 19 years, consisting of 8 albums (including Tin Machine), not a single Bowie record was written exclusively by him. These 'lost years' are the nadir of Bowie's career, in my opinion, and were exceedingly difficult to listen to. Aside from the screaming “I'm Afraid of Americans” from “Earthling” and some intriguing exploration on “1. Outside,” there's very little fruit born during this time.

It wasn't until 2002's entirely self-penned “Heathen” that Bowie finally, thankfully returned to form with sonic brilliance and legitimate artistic integrity. Lightning struck again thirteen years later with "The Next Day," which was an even more appreciable effort. Unfortunately, there was to be only one album after this.

STRANGE FASCINATION

Invariably, when others learned of my “Bowie Project,” I was asked the obvious questions. Those being, “What's your favorite album?” followed closely by “What's your favorite song?” Now that I've listened to every song on every album, I know, definitively, what they are. And I'm not too surprised that they remained the same after the project.

My favorite album continues to be “Hunky Dory.”

I know many, if not most, choose “Ziggy Stardust” which I totally understand. Is Ziggy, the well-hung cat with a screwed-down hairdo and snow-white tan, infinitely more captivating and mesmeric than David Jones tickling ivories on his piano? Of course he is, and that is why he existed and how he launched Bowie's colossal success as an international rock star.

Don't get me wrong, I love “Ziggy Stardust” and there's a reason this article starts with a line from that album. No one can deny that it is a legitimate heavyweight in the annals of rock and that it is a stupendously great collection of songs. Just as no one can deny that “Hunky Dory” is a slightly greater collection of songs. Interestingly, the songs for both albums were actually written simultaneously and the albums were recorded at, basically, the same time, so, in a very real sense, they are of the same burst of imagination and creativity.

My favorite song continues to be “Life on Mars?,” the crowning glory of "Hunky Dory."

In a near 50-year career, having written hundreds of insanely wonderful songs, it's extremely difficult for anyone to nail down their favorite. Narrowing it down to even a Top 10 is a nearly insurmountable feat. However, I always go back to “Life on Mars?” It truly is Bowie at his unequivocal zenith of songwriting.

The composition itself is so implausibly strong, it practically defies belief. However, when you add Rick Wakeman's dazzling piano and Mick Ronson's spellbinding string arrangement, it becomes absolutely transcendent - the masterpiece of a lifetime. It is positively unassailable and is one of the best rock songs ever recorded. Period. Oh, it also happens to be Bowie's favorite Bowie song as well.

LOOK AT ME, I'M IN HEAVEN

Bowie's final album, Blackstar, was released on his 69th birthday, January 8, 2016 – 3 days prior to his passing. I was aware of its release and, of course, Bowie's death, but I was unable to listen to it. It all seemed too immense, too final. If Bowie was forever gone, didn't that mean that something inside me had also ceased to exist? Simply put, it was fear that, sadly in retrospect, kept me away.

Fittingly, Blackstar is among Bowie's best and remains for me, and many others, one of my favorites, particularly the song “Lazarus,” which is about as poignant and beautiful as one can imaginably get (and is my 2nd favorite Bowie song). While virtually all music critics wrote effusively fulsome articles and showered the album with unfettered, much deserved praise, there is one particular aspect of Blackstar that transcends its status as a brilliant sonic artifact.

For me, the most wonderful and treasured part of Blackstar is that it exists as a vehicle to capture the last great art of a truly great artist. Moreover, it is a physical and aural manifestation of Bowie's perseverance and commitment to his art.

The gravity and magnificence of the album profoundly intensifies when one is made aware of the fact that a 68 year-old man, whose body is riddled with terminal cancer, stands up after a grueling chemotherapy session and literally walks directly into a recording studio to deliver an impassioned, completely flawless vocal performance.

In the documentary, “David Bowie: The Last Five Years,” longtime producer, Tony Vicsonti, plays the isolated vocal tracks from “Lazarus.” In these, one can clearly hear just how sick Bowie truly is. As he desperately struggles to draw breath, come the sounds of the painful rasping of his failing lungs, only seconds later to release a perfectly delivered lyric.

It is simultaneously harrowing and jubilant to hear.

It is the sound and emotion of a man, an artist giving all of himself over to his art; violently railing against the limits of his rapidly dying body in what he knows is a final expression of his heart, his very soul. It stands as one of the most triumphant, inspiring, and majestic moments in music and in art.

I intentionally made this the last song I played as part of the Bowie project for this very reason. It was when he sang, “Look up here, man, I'm in danger. I've got nothing left to lose,” that the floodgates were finally loosed and the tears came in hot streams. It was an intensely powerful moment. One characterized equally by grief, admiration, respect and celebration.

With still wet cheeks, I silently walked into my studio, sat down and put my guitar in my hands. I breathed deep and smiled inwardly as I thought if the old dog still had diamonds in him at nearly 70, then this insane lad may still have enough of Ziggy's stardust left to throw a few more thunderbolts and sparks himself. And I began to play...

And just like that bluebird, you're free. You're in heaven and everybody knows you now.

“Ain't that just like me,” indeed.

Thank you, Mr. Bowie.